resources

The GuariJío Indians of the Mayo river

Published in 2002

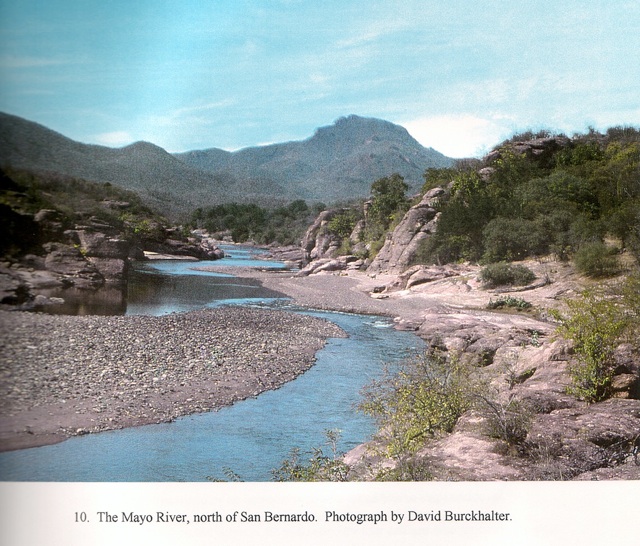

Sam Sedgwick, an Arizona rancher who enjoyed traveling in Mexico, made many trips between 1993 - 1998 to the Guarijío indigenous community in the mountains north of Álamos. He had learned of the Guarijíos through the writings of geographer and ethnographer Carl Sauer as well as through the cultural documentation provided by Howard Scott Gentry during Gentry’s travels in Guarijío country during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1942 Gentry published Río Mayo Plants of Sonora-Chihuahua, which became a classic work in the field of botany. What Sedgwick appreciated, though, was Gentry references to Guarijío culture and his understanding of people and social structure within this community.

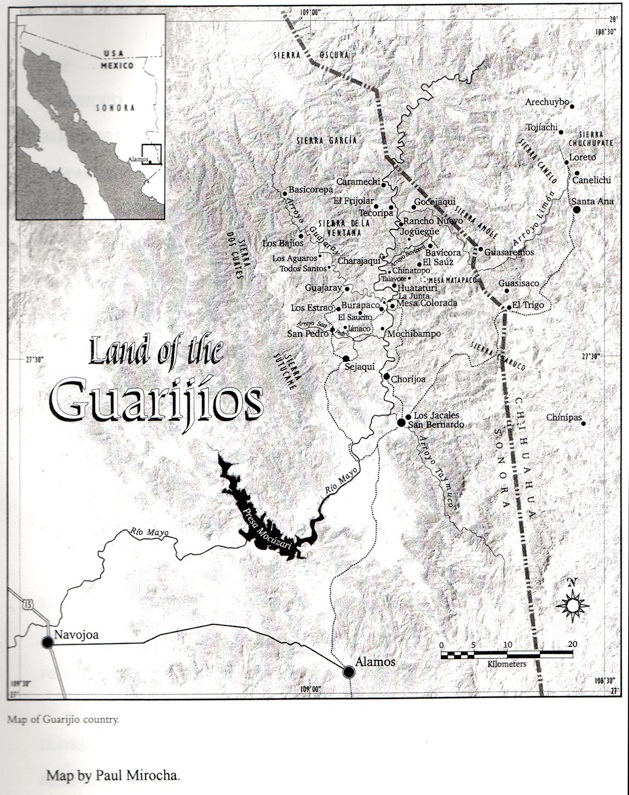

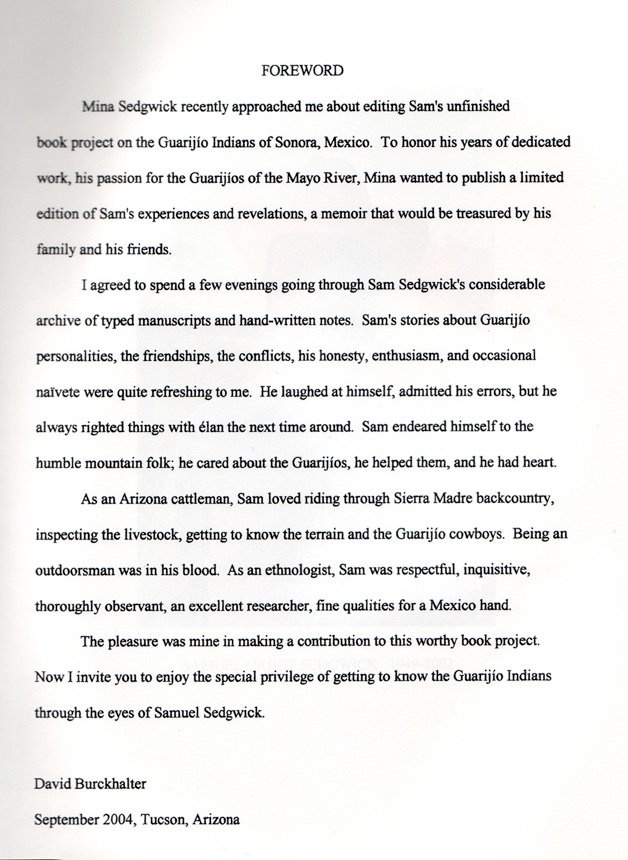

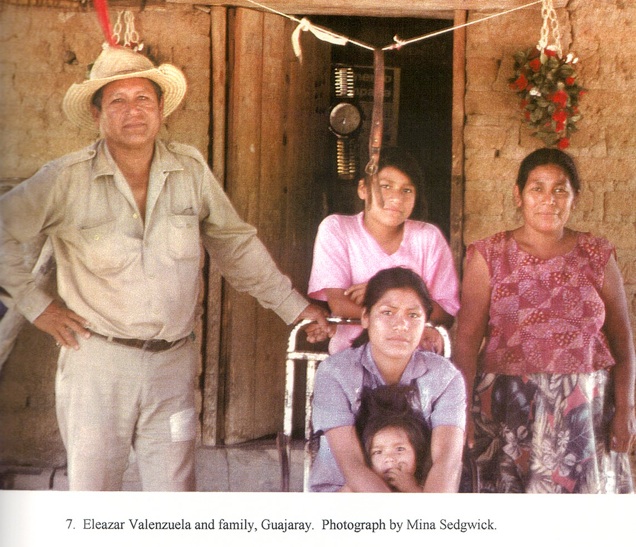

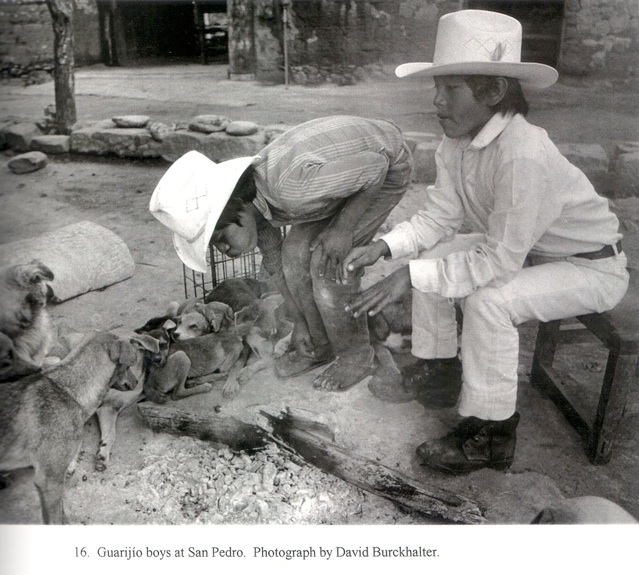

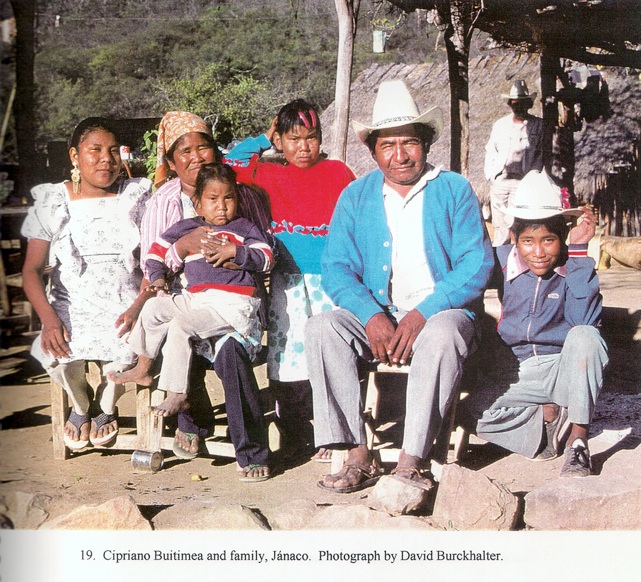

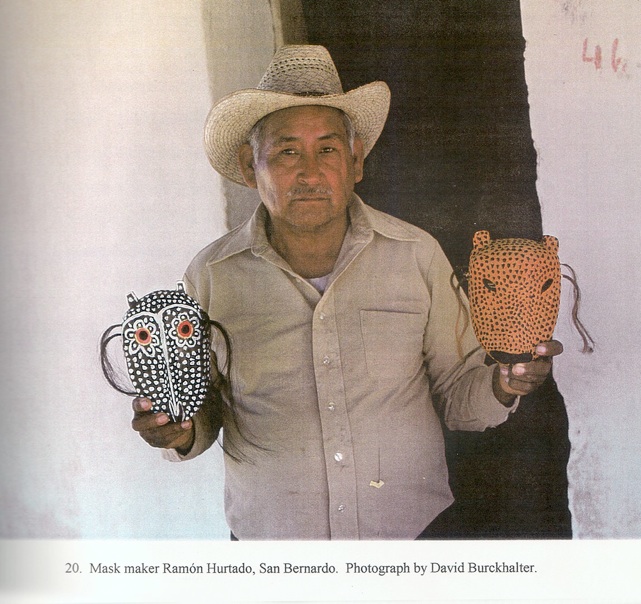

The Guarijío, who reside in numerous small communities north of San Bernardo, Son., have been suspicious of “outsiders” since the Spanish came in the 16th Century and introduced them to both a new religion and a new way of life. Their response was to go into hiding—the same response as their indigenous neighbors the Tarahumara—and their remote mountain environment enabled them to live into the 1970s much as their ancestors had done for hundreds of years before the Spanish arrived. When Sedgwick first approached the tribe in 1993, he needed the assistance of the community leaders (gobernadores) to gain access to the people. Sedgwick, in his introduction, thanks many of these governors for the success he had, including Rafael Méndez at Los Bajíos, former Instituto Nacional Indigenista director Leobardo Quiroz at San Bernardo, Ricardo Valenzuela Flores of San Bernardo, and Javier and José Zazueta of Mesa Colorado.

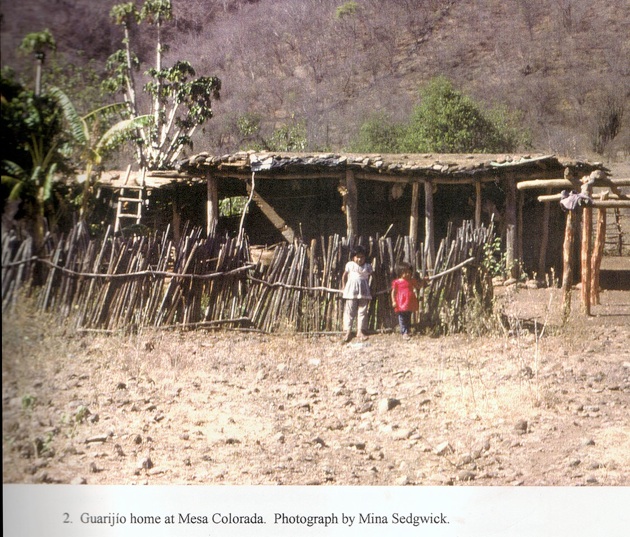

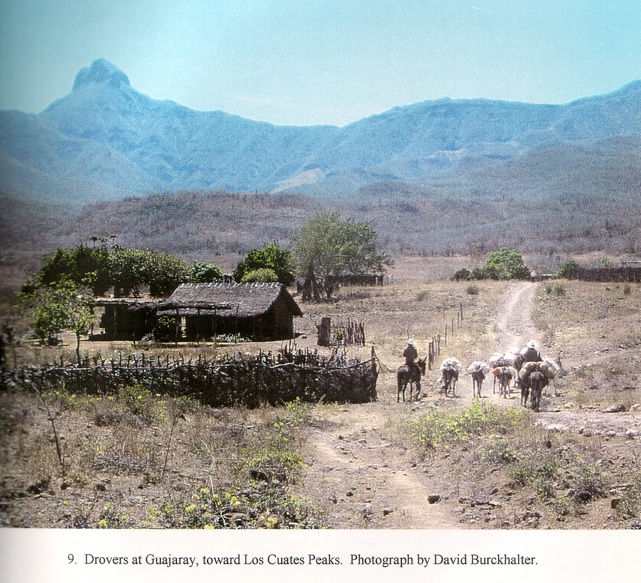

During his visits over a five-year period Sam tried to help the Guarijío improve the profitability of their ranches. They raised cattle in the high sierras, which they then sold to Mexican cattle traders at a very low price. Sedgwick’s plan was for the Guarijío ranchers to drive their cattle to a holding ranch in San Bernardo, then transport the cattle to the U.S. border by truck and sell them directly to American beef importers. Sedgwick had only limited success during the five years he worked with the tribe, but his ideas have had a long-term effect.

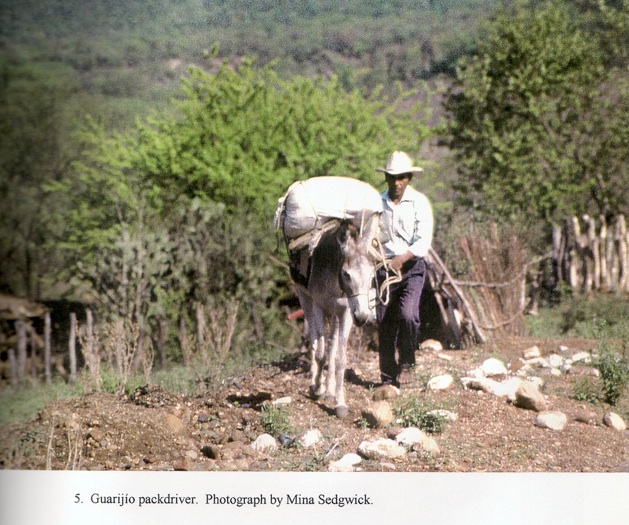

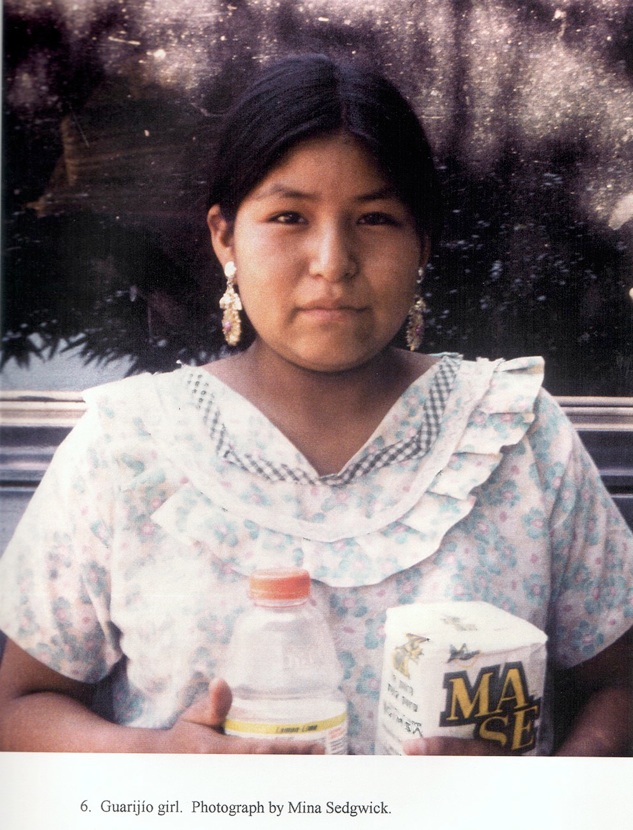

Sedgwick was also helped in this endeavor by his wife, the former Guillermina Arenas (Mina) whose parents lived in Navojoa, Sonora. Using Navojoa as a home base, it was much easier for him to make numerous trips to Mesa Colorado and beyond. His wife was often at his side on these trips, and when Sedgwick died in 2002 his wife was instrumental in getting his memoir published. Mina also provided many of the pictures used in the book.

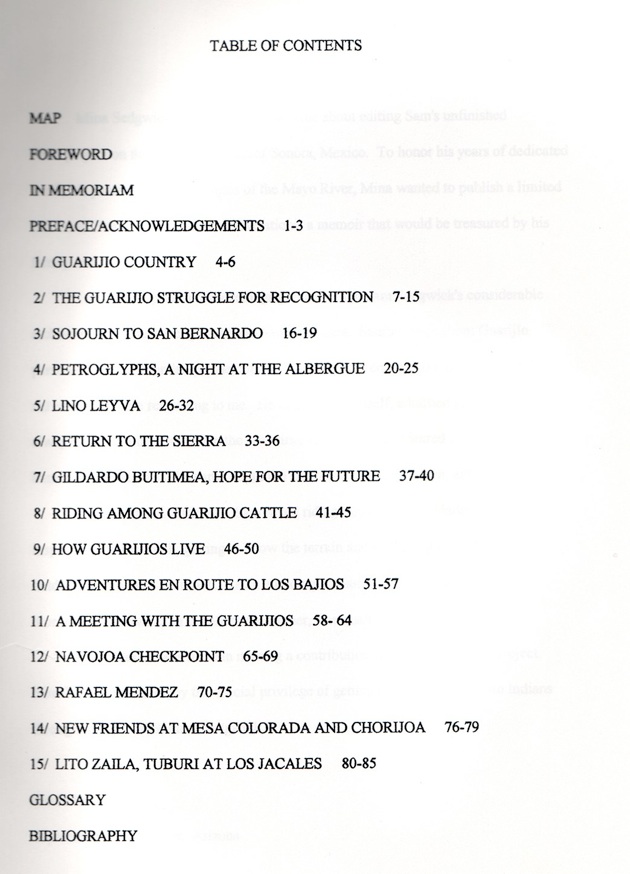

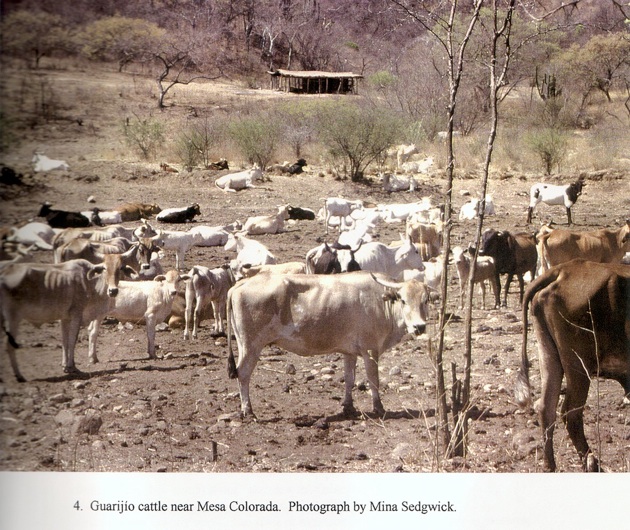

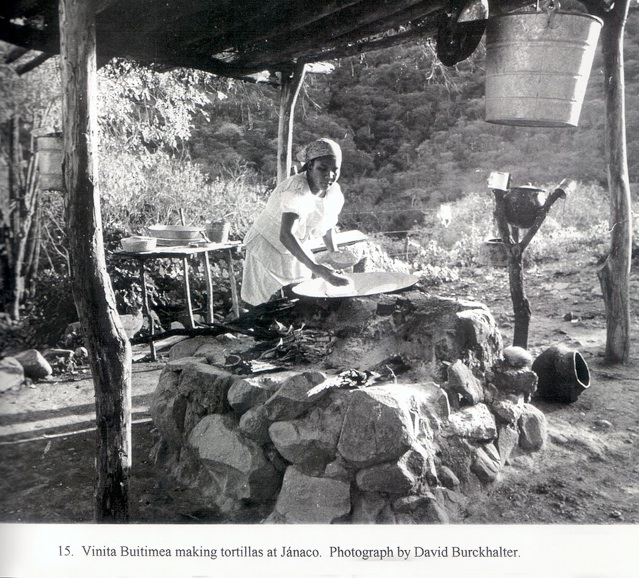

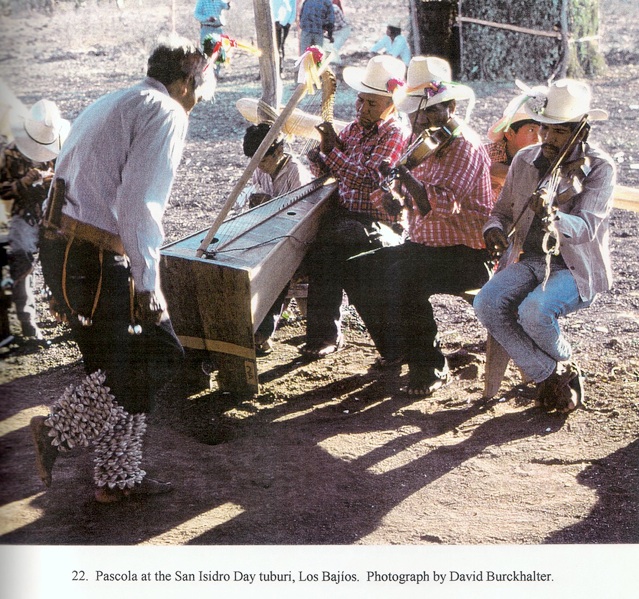

What stands out in the book is Sedgwick’s description of his travels by horseback into the Guarijío communities—especially those as isolated as Los Bajíos. This community of 200 was only accessible by horseback, a day’s ride from Guajaray and far from the conveniences of modern life. Sedgwick loved the people and their way of living in these remote mountain areas, and his goal was to bring a higher standard of living to Guarijío people.

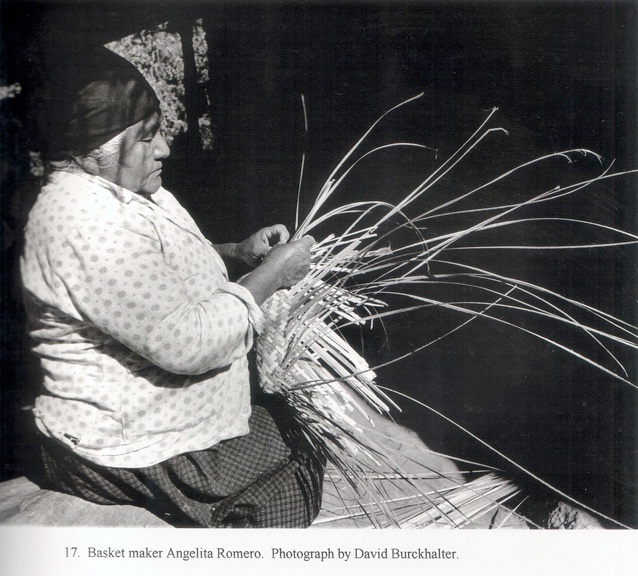

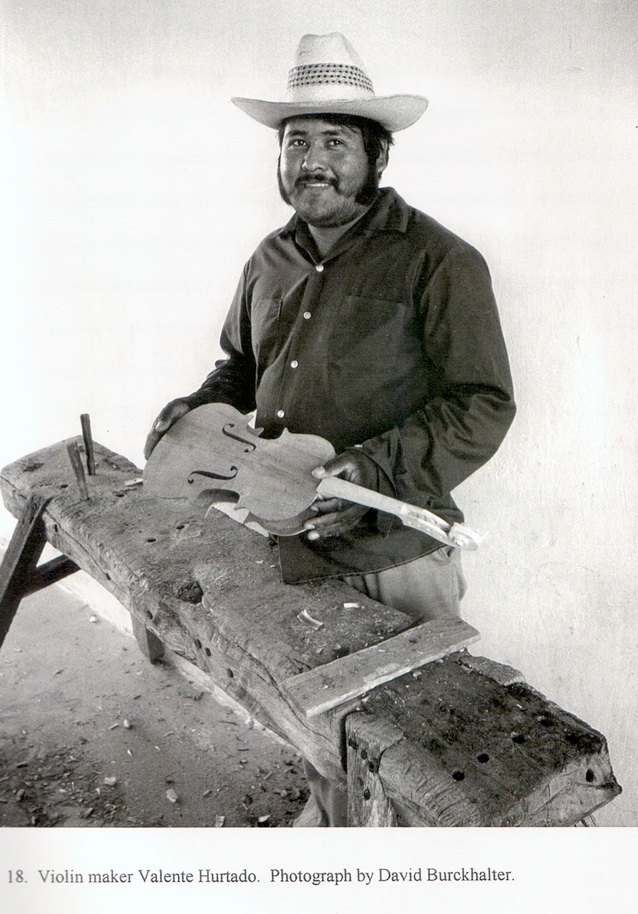

This book of 90 pages and 22 full-page photographs is available in the Álamos History Association research Library.

Sam Sedgwick, an Arizona rancher who enjoyed traveling in Mexico, made many trips between 1993 - 1998 to the Guarijío indigenous community in the mountains north of Álamos. His memoir of nearly 100 pages, plus 22 photographs, tells about Guarijío life and culture, and outlines his plan to help the tribe market their cattle.

The complete book can be read on site at our research library in Álamos.